1854 - Cholera in Colmar

The last epidemic of a long list and also the best documented as we can now see the figures in official documents as opposed to relying on accounts and legends. The records show that 505 people out of the total population of 21,348 were infected, 349 of whom died. Although in absolute terms the numbers do not seem so terrifying, the actual effect the epidemic had on the population was devastating. The disease had a profoundly traumatising effect on both those living in the depths of poverty and the people who thought they had the ways and means to halt its march. Was cholera a disease that struck only the poor who lived in conditions of abject hygiene ?

The last epidemic of a long list and also the best documented as we can now see the figures in official documents as opposed to relying on accounts and legends. The records show that 505 people out of the total population of 21,348 were infected, 349 of whom died. Although in absolute terms the numbers do not seem so terrifying, the actual effect the epidemic had on the population was devastating. The disease had a profoundly traumatising effect on both those living in the depths of poverty and the people who thought they had the ways and means to halt its march. Was cholera a disease that struck only the poor who lived in conditions of abject hygiene ?

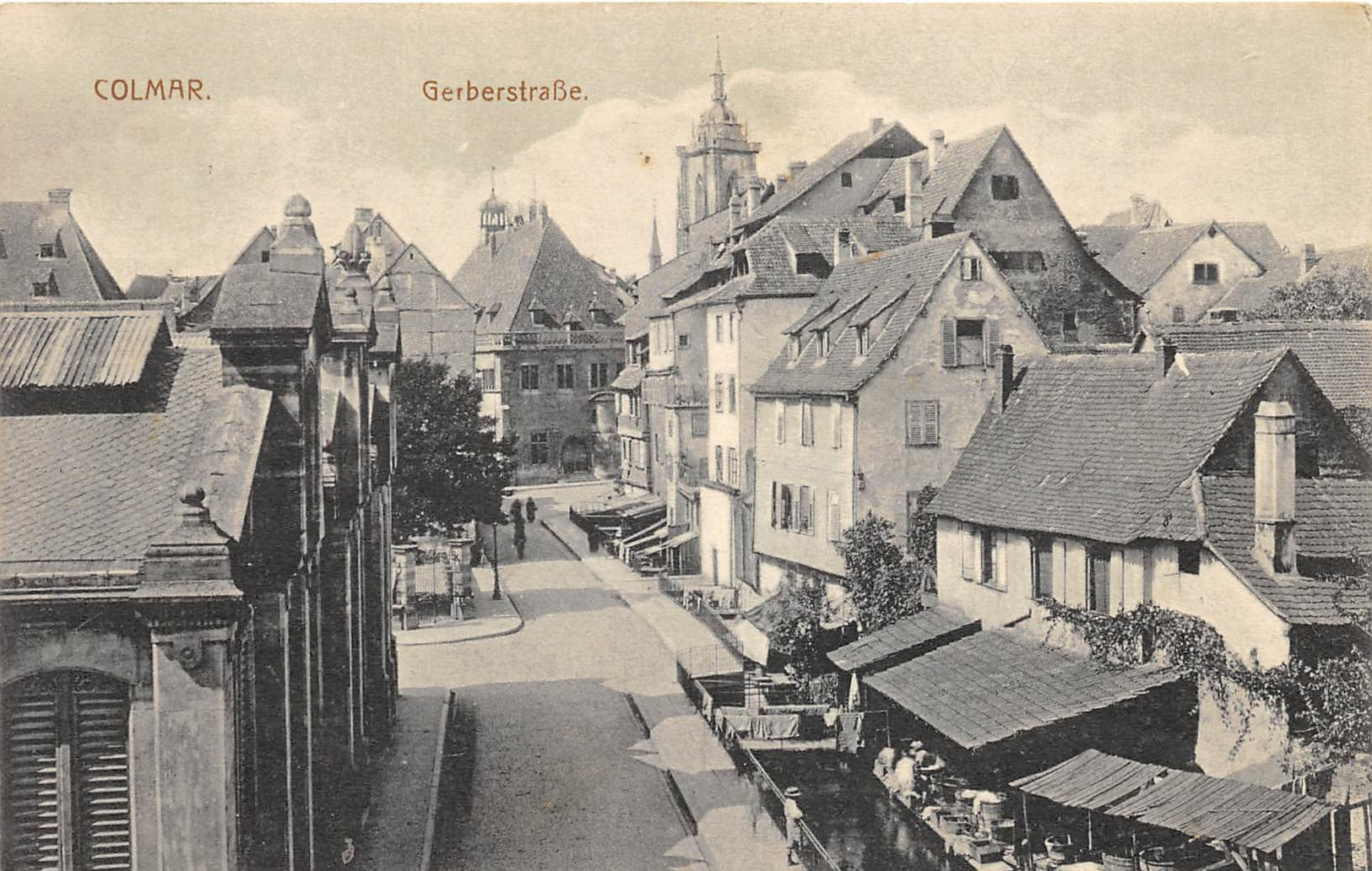

To all appearances, the answer was yes. Cholera was known to originate from Asia, hitting the world in six successive waves from 1817 onwards. Cholera was always transmitted orally and was carried in the water, the quality of which was therefore a determining factor in the spread of the disease. In Colmar, like everywhere else, water was used for drinking, cleaning and for washing food.

The reports from the 1830´s, when cholera was rife in Europe, painted an appalling picture. Documents of the Sanitary Intendance of the Upper Rhine showed that both rural and urban streets and houses were in a filthy state. Stables, dungheaps and latrines inside the houses created ideal conditions for the proliferation of the virus. Although public buildings were cleaned with chlorinated water and painted with lime, few private houses went to the same pains. Hygiene precautions recommended by the Mayor were largely ignored.

The hardest hit of all were the people living in narrow, airless streets like the rue de la Herse, rue de la Poissonnerie, rue de la Harth and rue Haslinger. 174 of the 349 people who died in the outbreak were factory workers and another 104 were day labourers. When a commission of enquiry was set up in the aftermath of the epidemic, its findings showed that few of the houses in the city had a cesspool, while faeces were often simply dumped in courtyards or thrown directly into the water running through the city. Essential water purification was continually being put off, with the city council not wanting to make itself unpopular with the local population by levying further taxes to cover the costs.

Visit

Visit